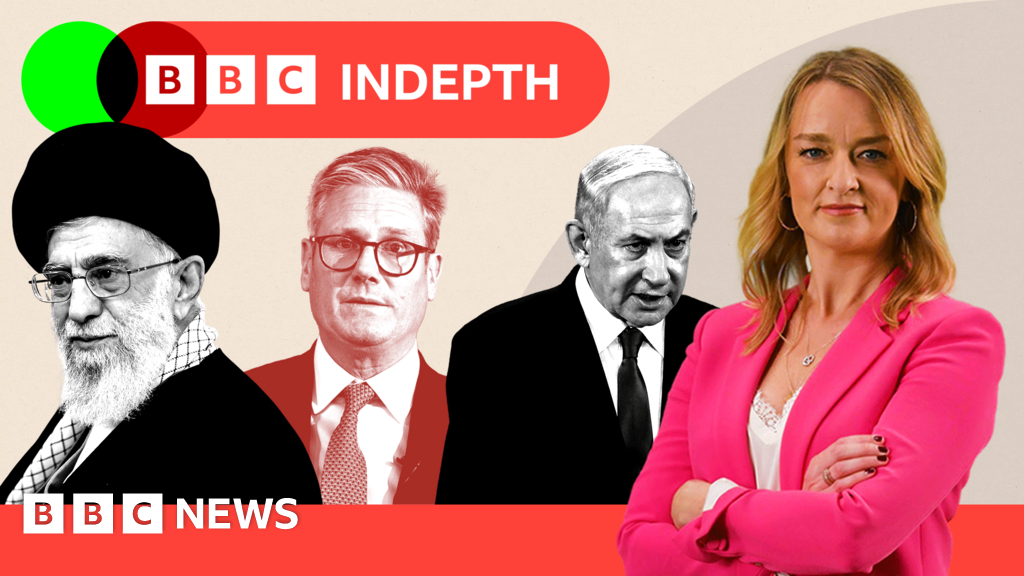

Why war in Middle East involves UK, BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg writes

BBC

BBC“Let’s be real, the war has started,” a former minister tells me. “What happens in the Middle East never stays in the Middle East.”

It’s hard not to be moved by the burning conflict – the killing of Israelis by Hamas almost a year ago and agony of the families of hostages snatched; the killing of thousands of Gazans by Israel in its response and the terrible suffering there.

And now Lebanon, where Israel has struck again after almost a year of cross-border hostilities, killing hundreds in air strikes against Hezbollah. Hundreds of thousands more civilians are on the move, desperate to find safety.

But it can feel bewildering, and far away. So why does it matter at home?

“There’s the humanitarian horror,” says a former diplomat. And of course there are many families in the UK worried about the safety of friends or relatives still in Lebanon, Israel and Gaza. There is a potential bump in the number of refugees likely to head for Europe from Lebanon if all-out war begins.

The conflict has stirred tensions here as well. “We see it on our streets,” the former minister says, whether that’s at Gaza protests, the rise in antisemitism or even a handful of pro-Palestinian politicians winning seats in Parliament.

If – as US President Joe Biden has acknowledged in public – Israel goes ahead and hits Iran’s oil industry, the costs could hit us all.

The price of oil jumped 5% after Biden’s remarks. Iran is the seventh biggest oil producer in the world. Just at a time when the world has been getting used to inflation cooling down, spiralling costs of energy could pump it right back up again and we’d all feel it.

One source suggested if the conflict keeps intensifying, “the Iranians might block the crucial Strait of Hormuz to show their power” which could, they suggest, “tip us into a 70s style crisis”.

Around 20% of the world’s oil passes through the narrow channel of water. “It’s the pocket book effect,” says another Whitehall source. The impact on the economy could be huge.

So what can the UK do about a hellishly complicated situation, especially with a new government that is still finding its feet? There’s the practical, the defence, and the diplomatic.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Foreign Office has chartered three flights to get Brits who live in Lebanon home – and a fourth is scheduled to leave Beirut on Sunday. There are extra military staff in Cyprus ready to provide extra help if needs be.

The UK is deeply involved in providing humanitarian help in the region and Labour made the decision to start money flowing again to the UN organisation for Palestinian refugees on the ground, UNWRA, once it moved into power.

UK military back-up

The UK military was there as back-up to help Israel defend itself against Iranian missiles this week. RAF Typhoons were in the air on Tuesday night ready to support Israel’s own defences. Israel also had support from the US.

In the end, the UK didn’t fire any of their weapons. But back in April, RAF Typhoon jets based in Cyprus shot down Iranian drones.

Yet there are nerves in Labour circles about how far that role might go now in the coming weeks. One senior MP said: ‘‘We can be there to help defend Israel, we can be America’s mate, but we must not be there in any way, however small, in attacking Iran.”

The UK is in what a former ambassador described as a “weird straddle”. Ministers are urging Israel to hold back its attacks across Lebanon, just as through the last 12 months they have asked Britain’s ally to stop pummelling Gaza. But at the same time, when called upon, helping Israel defend itself on specific occasions.

And even though some arms sales have been suspended, weapons continue to go.

Diplomatic opportunities

Then when it comes to the diplomacy, a former senior official tells me the UK is “thinking about the off ramps,” – in other words, encouraging all the players, not just its allies, to think about how to bring the conflict to an end, and what a post-war settlement might look like.

The UK has specific opportunities – there are things that it can do that the US can’t, with an embassy still in the Iranian capital Tehran, for example, whereas the Americans haven’t had any formal diplomatic relations with Iran since 1980.

“Diplomacy is not only about talking to your friends,” the former official says, suggesting the UK has a role to play in understanding Iran’s position and communicating it to others to ensure Israel and the US’s decisions “aren’t taken based on misunderstandings”.

The specifics of the UK’s position have been used to diplomatic advantage before.

A former minister tells me when the families of hostages from Israel were in London, a meeting was brokered between them and the Qatari chief negotiator, an encounter that couldn’t have taken place elsewhere given the state of relations between their two countries.

Another source says that when it comes to Iran, the UK “is not just a back-channel, we can be the front channel”. Foreign Secretary David Lammy held a phone conversation with the Iranian foreign minister in August.

Limits – and high stakes

There is a limit to the influence that can be brought to bear, not just because of the realities in the region.

The UK’s voice is important, but not a deciding influence – “the only critical external player is the US,” says one Whitehall source.

And fundamentally, perhaps the reality right now is that “no-one is scared of America any more,” as one senior government figure suggests. Months of urging restraint have not brought an end to the conflict – anything but.

Whether politicians in the UK have the appetite for greater involvement is worth asking.

Foreign policy rarely yields rewards for politicians at home in the UK – and it can also feel like a distraction having to travel the globe while dealing with rows over free gifts and winter fuel payments. Sir Keir Starmer has found himself “spending more time on a plane than he ever expected,” a senior MP suggests.

Diplomacy matters, whether its impact is easy to measure or not. A government insider suggests without the UK, US and Western allies urging restraint on a daily basis, there is a parallel universe where the conflicts might already have boiled over into a war far worse than anything we have seen so far. “Everybody has been working incredibly hard to try and prevent a spillover,” a senior figure says.

The question this weekend is whether a terrible conflict that sucks in the US and other powers can yet be avoided. How Israel chooses to respond to Iran’s attacks may prove decisive.

A lot is at stake: a wider conflict could wreak havoc on our economy, on the stability of the world, and as well as the terrible toll on civilians caught up in wars not of their own making.

“Our best labour is diplomacy,” a former minister says. The UK certainly cannot stop or solve this dangerous conundrum on its own. But the gravity of what is going on means that it has to try.

Top photo credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.

Related

Newspaper headlines: ‘Putin’s dirty work in UK’ and ‘Honeytrap spies’

The Times focuses, external on Donald Trump's latest comments about the war in Ukraine. Its headline quotes the US president, who said Vladimir Putin was "doing

‘This could end in World War Three,’ warns Trump as…

7 March 2025, 17:31 | Updated: 7 March 2025, 18:06 'This could end in Worl

Met Office ‘polar vortex’ update as temperatures to plummet

The weather is expected to quickly change after a spell of sunshineThe Met Office has warned that "colder weather is on the way."(Image: Liverpool ECHO)It is fo

British Pie Awards 2025: Naan better as kebab pie wins…

The Turkish-tinged creation by Boghall Butchers - which is celebrating its 50th year in business - won through in the newly-formed fusion category, which also f