‘You could call him polysexual’: Leigh Bowery and the taboo-busting subculture that shocked 1980s London

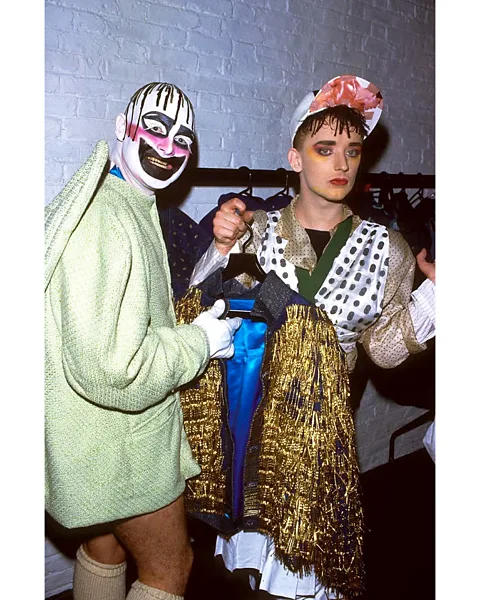

Brendan Beirne/ Shutterstock

Brendan Beirne/ ShutterstockFrom shocking performances to extraordinary costumes, how performance artist and style icon Leigh Bowery, and his fellow “outlaws and fashion renegades”, birthed a bizarre creative movement – and blazed a trail of chaos.

The 1980s: it was the decade of Thatcherism in the UK, and Reaganomics in the US. Generation X came of age; MTV showcased hot new talent like Madonna and Prince. Amid street protests and strikes, consumerism found an anthem in the movie Wall Street’s memorable mantra: “Greed is good”. And Joan Collins’ shoulder pads on Dynasty got bigger and bigger.

Brendan Beirne/ Shutterstock

Brendan Beirne/ ShutterstockMeanwhile, in London, a small group of flamboyant young hedonists were stirring a cultural melting pot. Audacious and experimental in their creativity and lifestyles, they would later be lauded as fashion trailblazers and creative visionaries. But for a few years in the 1980s, they were just having the time of their lives.

Holly Johnson, singer of Frankie Goes to Hollywood, recalls, in the book Outlaws, his desired style for a night out clubbing: “Marc Bolan’s androgyny and David Bowie’s bird of paradise Ziggy Stardust creation were huge influences – it was a very theatrical look and that’s what we aspired to as teenagers. We didn’t want to look like everyone else, we wanted to look fabulous.”

The book ties in with a new exhibition, Outlaws: Fashion Renegades of Leigh Bowery’s 1980s London, at the Fashion and Textile Museum in London. And Johnson is just one of those recalling the styles, sounds and escapades of the era. The show chronicles the life and work of Leigh Bowery, the performance artist, style icon and fashion designer who came to London from Australia in 1980, and rapidly became the centre of attention in any room, in his wildly original outfits and phantasmagorical make-up. Also explored in the exhibition is the subculture from which Bowery grew, full of “fashion renegades”, including designers John Galliano, Pam Hogg, Wayne Hemingway, Stephen Linard, BodyMap and Rachel Auburn.

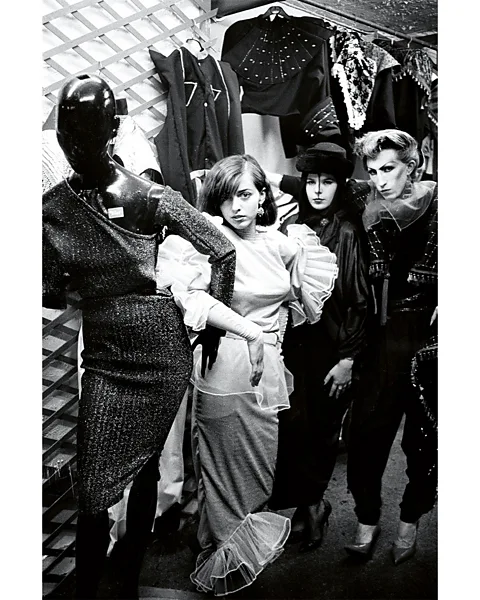

Sheila Rock

Sheila RockIt was a scene populated by late Baby Boomers (born 1946 to 1964), and some early Gen Xers (born 1965 to 1980) when the latest on what to wear and where to wear it was gleaned not from social media, but from reading physical magazines, like The Face, i-D and Blitz – all 1980s launches – or watching the BBC’s weekly music show, Top of the Pops.

The group were labelled Blitz Kids (after the club run by Steve Strange and Rusty Egan at Blitz Wine Bar in Covent Garden), or New Romantics (to include bands like Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet). It found its creative outlet in the realms of fashion, art and music – and, importantly, in the “the anarchic energy” of London’s club scene, Outlaws co-curator Martin Green tells the BBC. “Every time you went out, everyone was dressed in a new outfit, things they’d made or bought at Kensington Market.” It was a time pervaded by “an incredibly creative force, very exciting, very progressive.”

“What was so vital was the physical experience,” says NJ Stevenson, Green’s co-curator. “The desire to come to London, reinvent yourself and make your own luck was visceral.”

Hemingway – who recently co-founded vintage business Charity Super.Mkt – believes the 80s has been “massively influential” because it was “the first time youth culture was very heavily documented by the mainstream media”. He and future wife, Gerardine, sold their self-made clothes in Camden Market – a venture that became global fashion brand Red or Dead.

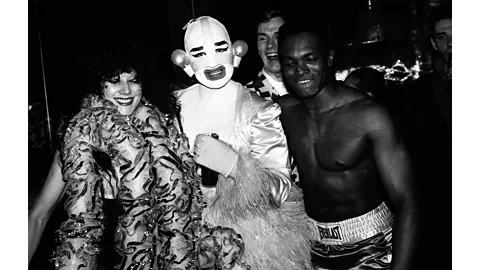

Joan Burey

Joan BureyClubbing and posing were their main pastimes, Hemingway recalls fondly: “It was like a fashion parade to get into the clubs. We spent a lot of time getting dressed, looking in the mirror, changing – much more than my kids ever did.” He adds: “I can see the attraction of that time [for today’s youth]. Back then we were looking to and selling clothes from the 1940s. So to young people now, the 80s are utterly exotic.”

‘Modern art on legs‘

The biggest, boldest star on the scene, though, had to be Bowery. He was “modern art on legs” as his friend Boy George put it, and his unique persona provided rich material – he posed for many artists and photographers, including Lucian Freud, and he once became a living installation, in the window of the Anthony d’Offay Gallery. His collaboration with dancer choreographer Michael Clark resulted in some memorable looks, including Bowery’s bottomless leotard, worn by Clark on stage at Sadler’s Wells, as cacophonous post-punk band the Fall played live.

Bowery’s performances provoked both praise and revulsion – his commitment to shock was unswerving. In his infamous “birthing” act, performed at the nightclub Kinky Gerlinky in 1990, among other venues, he came on stage with a naked woman strapped to his body, and simulated giving birth to his “baby”, complete with fake blood and a string of sausages representing the umbilical cord. He married his co-performer in the act, Nicola Bateman, seven months before his death from Aids in 1994, aged 33. It was a performance that later inspired Rick Owens’s “human backpack” show of 2016, when the designer sent another model strapped to the walking model down the catwalk in several of the looks.

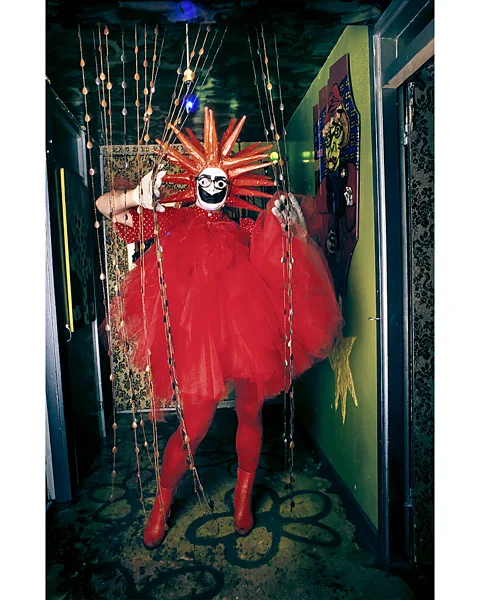

Fergus Greer

Fergus GreerSoon after Bowery’s death, John Richardson wrote in the New Yorker of the performer’s “disquieting” aspect. “Thanks to his twisted imagination and wit, he was able to soar above modish trashiness and establish himself as a subversive artist – a painstakingly meticulous craftsman who was also a latter-day Surrealist.” And Bowery’s vivid legacy can be felt in fashion ever since, and seen in RuPaul’s Drag Race queens. A second exhibition, wholly devoted to him, opens at London’s Tate Modern in February: it covers his “influence on figures such as Alexander McQueen, Jeffrey Gibson, Anohni and Lady Gaga”. McQueen’s red lace dress with matching full head mask, worn by Gaga in 2009, is testament to that.

Bowery was a central figure at Taboo, a London nightclub that opened in 1985, where the ethos was that nothing was taboo, and to “dress as though your life depends on it or don’t bother”. The Taboo doorman famously would present a mirror to unsuitable clubbers trying to enter, and witheringly ask, “would you let yourself in?”. It was “unpredictable, unabashed and unforgettable,” says Green. A magnet for pop stars and the fashion set, Taboo was known for its “defiance of sexual convention” writes Dylan Jones, Taboo regular and author of Sweet Dreams: The Story of the New Romantics. Bowery, Jones tells the BBC, “created a third sex for a time, you could call him polysexual… he created a very odd, transformative, transgressive persona”.

John Simone

John SimoneDavid Holah and Stevie Stewart, the duo behind 80s label BodyMap, went to Taboo “religiously every week”. Their sporty clothing made from Lycra and sweatshirt fabric was “all about the silhouette and made for every body shape,” Stewart tells the BBC. Their debut 1984 catwalk show featured models who were “larger people, older people, children… Diversity was key”.

“People would wear a bit of designer, say, Vivienne Westwood, with charity buys or Top Shop. It was home-made, mixed up,” says Holah who today teaches printmaking, while Stewart still makes clothes and is also a stylist working with Kylie Minogue among others. While BodyMap was around, the brand, like their cohorts, wanted to push fashion boundaries; the socio-political backdrop – the miners’ strike, environmental issues, protest and 1960s psychedelics – “all became part of the work”.

Also exploring this time and place is The 80s: Photographing Britain, at Tate Britain in London from November. Ingrid Pollard and Franklyn Rodgers and Wolfgang Tillmans are just three photographers featured who “used the camera to respond to the seismic social, political shifts” in the UK during the 1980s, including the Aids pandemic, and Section 28 – a 1988 law that prohibited UK schools and libraries from the so-called “promotion” of homosexuality.

Looking back at the 80s today, Green says: “there’s definitely a link between that queer culture and gender mixing and exploring of gender which was happening then, and which is again happening now”.

Derek Ridgers/ Unravel Productions

Derek Ridgers/ Unravel ProductionsSubcultures don’t have the chance to develop now as they did in the 80s, argues Hemingway. “We were a tiny set, just a few hundred people who went to these clubs, so a movement like that could stay underground. Now you’ve got the internet, and social media – trends become mainstream quickly. Anything wild wouldn’t be wild in 48 hours – it would be everywhere.” The dearth of nightclubs now is also part of the problem, he adds. “What’s the point of dressing up like we did, with nowhere to go?”.

“Fashion today is probably not as exciting visually as it was in the 1980s, but it’s exciting in its societal change and values,” he says, “like caring for the environment – people who work for us at Charity Supermarket take a real pride in never buying new clothing. In the end, fashion is about you, how you feel, what makes you happy. That much has not changed.”

Related

High street fashion giant to close 35 stores in just…

SelectFashion, the popular women's fashion retailer known for its affordable, trendy clothing, is set to close 35 stores within days, following a series of clo

Paris Friday: Victoria Beckham, Issey Miyake, Kenzo, and Róisín Pierce

One ranged from a gilded embassy or under the Louvre to an elegant br

Hillingdon woman adapts clothes to help neurodivergent shoppers

Ms Rule is a special educational needs coordinator at Douay Martyrs Catholic Secondary School in Hillingdon but works on her business in the evenings and at wee

British fashion creators accuse Chinese retail giant Shein of using…

British fashion is under threat from artificial intelligence that can identify popular products and flood the market with cheap copies, designers have warned.Fu