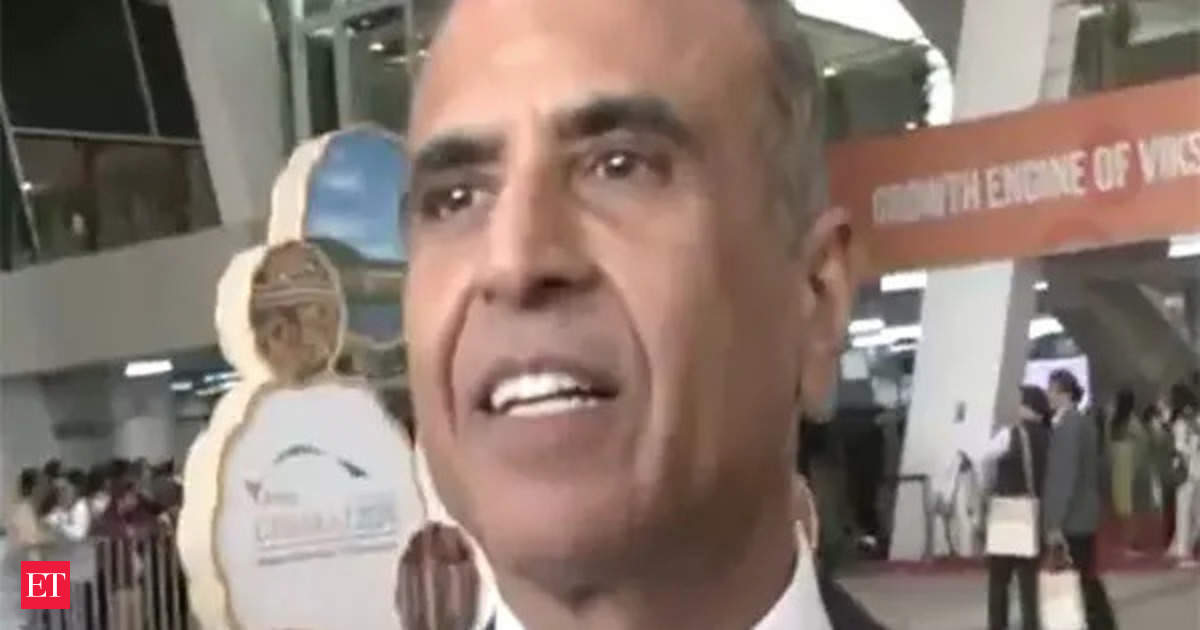

View: An Indian billionaire bets on overcoming UK NIMBYs

For one, it’s the first big corporate wager on Keir Starmer’s promise to “take the brakes off Britain.” Mittal has said in the past that “the telecom business is about three things: network, network, network,” and BT’s plans do mesh with that belief. BT’s slow buildout of Britain’s broadband backbone, through Openreach Ltd, may eventually deliver a stable revenue stream.

Mittal mentioned “the tremendous amount of physical infrastructure” that BT already has in the UK. But Bharti’s investment will really pay off if that infrastructure can get added to swiftly and predictably. Whether it is mobile 5G – which the BT Group now offers through EE Ltd. – or broadband connectivity through its wholly owned subsidiary Openreach,Bharti’s investment will pay off handsomely if Starmer does indeed get Britain building again.

Bharti, and its mobile brand Airtel, have had to learn how to navigate fraught political waters. In India, for example, it fought a doomed rearguard action against the blacklisting of Huawei 5G equipment. Airtel had a long relationship with the Chinese manufacturer, and in 2019 Mittal himself insisted – on stage with both the Indian and the U.S. commerce ministers – that Huawei was simply better quality than its competitors. Shortly thereafter, however, Indian regulators – while stopping short of an outright ban – pushed Bharti towards European suppliers instead. Mittal complied. Over two decades, Indian telecom companies have learned not to underestimate how tightly infrastructure and politics are linked.

But, in spite of that, they have managed to build out one of the world’s most accessible and cost-effective communications networks. You can get a decent 5G signal almost anywhere in that vast country now.

The UK desperately needs some of that edge. Some surveys have ranked London dead last out of 10 European capitals on its 5G availability. The difficulty of getting planning permission in NIMBY Britain for anything from a small cell tower to fiber cables is almost certainly the central problem. As my colleague Matthew Brooker has argued, Britain’s planning system is based on discretion, rather than rules. Too many people can veto or delay the smallest improvement. BT Chief Executive Officer Allison Kirkby agrees, pointing out that 80% of Swedish homes have full-fiber connections, thanks to more rational planning legislation. Here, only about 43% of houses older than 1995 – the overwhelming majority of Britain’s housing stock – have been connected.It sounds to me like a bit of Indian telecom infrastructure-building capability is just what Starmer-era Britain needs. It’s a unifying issue, if ever there was one: If you think connectivity in London is bad, you should try the country. In the pleasant Thames Valley town in which I live, this week’s farmers’ market was a disaster because nobody’s card machines could catch a cell signal. (And, of course, all the bank branches shut down last year, taking their ATMs with them.) Upset at my inability to buy a wagonload of artisanal cheese, I went home to check why this routinely happens and discovered a familiar story: An EE mast was struggling to be granted planning permission. Would you bet on a country where a man’s card can’t buy him cheese? Bharti has. Let’s hope Starmer wins him his bet.

(Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this column are that of the writer. The facts and opinions expressed here do not reflect the views of www.economictimes.com.)

Related

Best Crypto Casinos UK – Top 10 Bitcoin Gambling Sites…

Despite its overwhelming popularity, crypto gambling in the UK remains in a legal gray area. All casino operators in the UK need to have a valid permit, as requ

Online gambling channelisation in the UK – How well it…

Gambling in the UK is controlled under the Gambling Act 2005. This act requires all gambling operators to be licensed and regulated by the UK Gambling Commis

UK Gambling Commission Opens White Paper Public Feedback | Suffolk…

The UK Gambling Commission (UKGC) has initiated its third consultation period to gain feedback and proposals to make gambling machines in the UK more secure a

Paddy Power High Court case: Gardener wins £1m payout

Mrs Durber sued PPB Entertainment Limited, which trades as Paddy Power and Betfair, for breach of contract and for the rest of her winnings, based on what she w